In winter, that is from

the first of November until Easter, the brethren shall rise at what is

calculated to be the eighth hour of the night, so that they may sleep somewhat

beyond midnight and rise with their rest completed. If any time remain after

Matins, let the brethren, who are lacking in knowledge of the psalter and

lessons, employ it in study. From Easter to the aforesaid first of November let

the hour of rising be so arranged that there be a very short interval after

Matins, in which the brethren may go out for the necessities of nature, to be

followed at once by Lauds, which should be said at dawn.

Rule of St Benedict, Chapter 8

I noted in my previous post that Matins is traditionally said in the very early morning hours, while the world is still shrouded in darkness.

I thought it might be helpful to expand in this theme a little, by way of encouragement to try and say it (or whatever part of it you end up saying) before first light if you possibly can.

When Matins is properly said

In the traditional Roman Office, Vigils was literally said at midnight; St Benedict made it rather later, but on the basis that the monks would not go back to bed after saying it.

If you visit some of the traditional monasteries, such as Le Barroux, you can have the privilege of joining the monks in the very early hours of the morning in darkness, and enjoy the full symbolism associated with the hour. Getting up once or twice while on retreat of course, is one thing; doing it every day is quite another! Few laypeople can really make a timetable like theirs (starting Matins at 3.30am each day) work.

Still, there is a lot of symbolism embedded in the hour and the traditions around it that are, I think, worth being aware of.

Scriptural exemplars

Prayer at night seems to have been part of the earliest Christian tradition: Tertullian (c155-240), for example, talks about the ideal of being able to share the nightly prayers with one's wife if she is a Christian, rather than having to go to another room for this purpose.

And a number of early treatises on prayer and monastic rules point to Scriptural examples of the practice of praying in the middle of the night as rationales for the hour:

- it was in continuity with Old Testament practice attested to by Psalm 118 ('At midnight I rose to praise you'), a rationale also quoted by St Benedict in Chapter 16 of the Rule;

- the widow-prophetess Anna's presence in the Temple praying day and night (Luke 2); and

- Paul and Silas, praising God at midnight (Acts 16:25).

St Bede the Venerable also argued for continuity with the Temple tradition, pointing to Nehemiah 9's references to four 'hours' at the Night (viz Vespers, Compline, Vigils and Lauds) and four day hours.

Rising each day with Christ

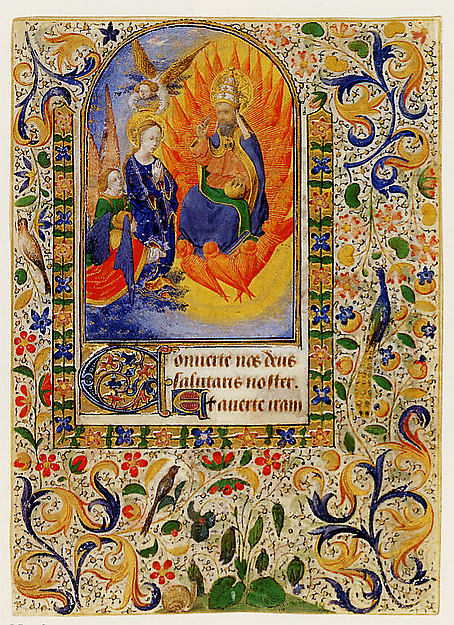

The most important reason for the hour, though, was probably the association with watching for the Resurrection and the Second Coming.

St Benedict starts his discussion of the Benedictine Office in Chapter 8 of his Rule. He then starts to discuss the Night Office, which he elsewhere treats as the eighth and last of the hours, rather than the first. And he opens by instructing his monks to rise at the eighth hour of the night to say it.

There is clearly something important that St Benedict is trying to signal here, around the symbolism of the number eight. The most important of those associations is perhaps with the Resurrection, the 'eighth day'. If you have been saying the opening section of Matins each day, as I've suggested, you might have noticed the Resurrection theme in the first psalm of the day, Psalm 3:

6 Ego

dormívi, et soporátus sum: * et exsurréxi, quia Dóminus suscépit me.

|

I have

slept and taken my rest: and I have risen up, because the Lord hath protected

me

|

There is a bit of a play in this verse, I think, both on the idea that sleep each night is a little death, and waking a little resurrection each day, as well as an allusion to Christ's Resurrection. And the verse is a direct response, I think, to Psalm 4 at Compline:

9 In pace in idípsum * dórmiam et requiéscam;

|

In peace in the self same I will sleep, and I will rest

|

So the hour early sets up a reference to the time it is properly said, and points us towards the hour of the Office, Lauds, where the Resurrection is made clear to the world.

Watching for the Second Coming

There is also an association, though, in early Christian thought, between the 'eighth day', and the Second Coming: in St Paul, both the day of the Resurrection and the Parousia are described as 'the day of the Lord'. Christians pray at night because:

...the day of the Lord will come like a thief in the night. It is just when men are saying, All quiet, all safe, that doom will fall upon them suddenly, like the pangs that come to a woman in travail, and there will be no escape from it. Whereas you, brethren, are not living in the darkness, for the day to take you by surprise, like a thief; no, you are all born to the light, born to the day; we do not belong to the night and its darkness. We must not sleep on, then, like the rest of the world, we must watch and keep sober; night is the sleeper’s time for sleeping, the drunkard’s time for drinking; we must keep sober, like men of the daylight. 1 Thess 5

St Benedict's contemporary Caesarius of Arles (470-542), opens his rule for nuns by comparing them to the wise virgins waiting with lamps trimmed and a good supply of oil (to be interpreted as good works of good works) for the bridegroom who arrives at midnight in the Gospel parable in

St Matthew 25.

Clement of Alexandria (150-215) also used this image, but applied it to men as well, in imagery echoed in St Benedict's Rule in relation to sleeping arrangements and readiness for the Night Office (

chapter 22):

We must therefore sleep so as to be easily awaked. For it is said, Let your loins be girt about, and your lamps burning; and you yourselves like to men that watch for their lord, that when he returns from the marriage, and comes and knocks, they may straightway open to him. Blessed are those servants whom the Lord, when He comes, shall find watching. For there is no use of a sleeping man, as there is not of a dead man. Wherefore we ought often to rise by night and bless God. For blessed are they who watch for Him, and so make themselves like the angels, whom we call watchers. But a man asleep is worth nothing, any more than if he were not alive. (The Instructor)

By St Benedict's time, the idea that all Christians ought to rise for midnight prayers had given way to practicality, and instead we have several examples of the hour taking on a particularly monastic character, reflecting the idea that religious watch on behalf of us all, and particularly on behalf of those who support their particular monastery. That idea is, I think, implicit in St Benedict's Rule, but spelt out much more clearly in several other contemporary sources. Caesarius' Rule for his nuns, for example, which St Benedict quotes from in a couple of places, effectively suggests that because Caesarius had established the monastery for them, the nun's prayers will make up for his own deficits, and he will be led into heaven by the wise virgins who will light his way:

Because the Lord in His mercy has had deigned to inspire and aid us to found a monastery for you, we have set down spiritual and holy counsels for you as to how you shall live in the monastery according to the prescriptions of the ancient Fathers. That, with the help of God, you may be able to keep them, as you abide unceasingly in your monastery cell, implore by assiduous prayer the visitation of the Son of God, so that afterwards you can say with confidence: “We have found him who our soul sought” (Cant 3:1, 4). Hence I ask you, consecrated virgins and souls dedicated to God, who, with your lamps burning, await with secure consciences the coming of the Lord, that, as you know I have labored in the constructing of a monastery for you, you beg by your holy prayers to have me made a companion of your journey; so that when you happily enter the kingdom with the holy and wise virgins, you may, by your suffrages, obtain for me that I may not remain outside with the foolish. As you in your holiness pray for me and shine forth among the most precious gems of the Church...(ch 1)

The Rubrics

All of this leads us to the practical problem of, if you are going to say Matins in the Benedictine form (or some version thereof), and not just leave it to the monks and nuns to say on your behalf, when to do it!

The rubrics for the 1963 Office basically say (and I'm paraphrasing a bit here, not giving you a word by word translation) that the Canonical hours of the Office are meant for the sanctification of the various hours of the natural day...Accordingly they should be said as close to the time as possible to the time which the hour represents General Rubrics, Book II, 137).

It then goes on to say that those who have an obligation to say the Office (ie priests, religious etc) need to say all of the hours within a twenty-four hour period (138).

Matins, it says, for a just cause, can be anticipated and said the day before, but not before fourteen hundred hours (139).

Options

There are a number of different practices which I've seen used in monasteries in relation to Matins which you could consider:

- say it the night before. This used to be fairly common, but I'm not sure that any monasteries still do this;

- say it at midnight then go back to bed - this at least preserves the night character of the hour;

- say it at a fixed early hour of the morning such as 3.30am;

- adjust the start time with the seasons as St Benedict suggests, but with only a short break before Lauds winter and summer to allow more time for sleep; or

- say it first thing in the morning immediately before Lauds, not necessarily entirely in the dark.