|

| Vespasian Psalter, c8th |

And the time that remains after the Night Office should be devoted to study by those brethren who still have some of the Psalter or lessons to learn.

Rule of St Benedict, ch 8

In the previous post I provided the rubrics for the psalms and antiphons and talked a little about their importance in the Benedictine Office. Today I want to move onto some of the issues around picking a psalter and psalm translation to use.

Tomorrow I will start providing some reviews of the various books, but in order to make your choice you need to know a little about the various translations.

And on this topic, no matter what version you (think you) are planning to use, please indulge me for a few minutes and at least read through this post!

English versions of the psalms

I know from the survey (thanks to those who have done it) that quite a few readers plan on praying Matins in English (or another modern language) for various reasons.

Now the simplest option for doing this is of course to use the

Monastic Breviary Matins book, which uses the King James Version.

I will go into the pros and cons of this book more fully in another post, but let me point out two key issues with it upfront.

First, no matter what book you use for the other texts of the Office, and whatever denominational background you come from, I strongly recommend using a translation of the psalms based on the Septuagint rather than the Hebrew Masoretic Text. I will set out the reasons for this below.

Secondly, if you are a Catholic, you really should be using a translation of Scripture that has been officially approved (and ideally for liturgical use in your country). The King James Version is not in that category.

How different are the various versions?

For many of the psalms, the differences between the two main translation traditions are not that different. But for some very important psalms the differences are absolutely crucial.

Consider, for example, the case of Psalm 59 (60), the first psalm of Wednesday Matins. The Vulgate translation of verse 3 is as follows:

Ostendísti pópulo tuo dura: potásti nos vino

compunctiónis.

The Lewis and Short definition of

compunctio is a puncture, or the sting of conscience, remorse. Accordingly the Douay-Rheims translation of the second phrase, referring to the wine of sorrow doesn't quite convey the idea of a call to repentance fully in my opinion, but isn't too far off:

3 Ostendísti pópulo tuo dura: * potásti

nos vino compunctiónis.

|

5 You have shown your people

hard things; you have made us drink the wine of sorrow.

|

In fact on this verse the Knox translation is probably better:

Heavy the burden thou didst lay on us; such a draught thou didst brew for us as made our senses reel.

The King James Version of this verse though is rather different:

Thou hast shewed thy people hard things: thou hast made us to drink the wine of astonishment.

And the Authorized Version used in the Lancelot Andrewes Monastic Breviary Matins is even further still from the Vulgate:

Thou hast shewed thy people heavy things; thou hast given us a drink of deadly wine.

I actually think this matters quite a lot, given that the overall theme of Wednesday in the Benedictine Office is the remembrance of Judas' betrayal, and the establishment of the Church as a vehicle for reconciliation of mankind.

Why the Septuagint-Vulgate tradition?

For centuries the Catholic Church has used the Latin Vulgate psalter translated from the Greek Septuagint for liturgical and other purposes. The Septuagint translation was made in turn from the third century before Christ.

There are, in my view, strong arguments for using translations based on this tradition rather than those based on the Hebrew Masoretic Text such as the KJV/Authorized Version and 1979 neo-Vulgate.

The short version is that St Jerome - and Luther - were wrong on this issue; the Septuagint was a providentially given translation that is integral to the tradition of the Church, and its integrity and authenticity has now been borne out by the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The slightly longer version you can find below in relation to the use of Latin. In terms of the Septuagint-Vulgate vs neo-Vulgate debate, I've written a little more on this topic from a Catholic point of view

here.

For those coming from an Anglican, Lutheran or other perspective, an excellent presentation of the issues aimed at a general audience can be found in Timothy Michael law's book

When God Spoke Greek.

And for a general online introduction to the topic I would highly recommend a little series by Fr Hunwicke which starts

here.

The case for Vulgate Latin

I also want to strongly suggest learning to say the office in Latin.

You do not need to formally learn Latin in order to pray in it.

Rather, I am suggesting learning how to pronounce it, and work with a reasonably literal translation of the Vulgate, such as the Douay-Rheims, to help you understand it, and gradually build your knowledge of it over time.

But why bother? Here goes:

(1)

The rubrics: For Catholics, the 1963 rubrics in my view require the use of Latin if you want to pray the Office liturgically (with the possible exception of the readings to which I'll come in due course). Even if you plan to start by just praying it devotionally, gradually learning how to say the Latin gives you an additional option.

(2)

Seeing the connections to the Benedictine Rule: St Benedict's Rule draws heavily on the psalms, and in my view, he has also organised his Office in ways that reflect some of the themes set up in the Rule. Those connections are much easier to see if you use the Latin rather than English.

A good example is the use of the word 'suscipio' and its derivatives which means sustainer or upholder. In his description of the monastic profession ceremony, St Benedict has the novice repeat a verse from Psalm 118, the 'Suscipe' three times:

**116 Súscipe me secúndum elóquium tuum, et vivam: * et non

confúndas me ab exspectatióne mea.

|

116 Uphold

me according to your word, and I shall live: and let me not be confounded in

my expectation.

|

But St Benedict also uses the word many other times in the Rule in ways that suggest connections between these usages - in relation to the teaching of the abbot and the reception of guests for example. In doing so, he is almost certainly drawing on both St Cassian, and several of St Augustine's expositions on the several levels of meaning of this word. And to reinforce the importance of these concepts, St Benedict sets psalms that use this key concept at the start and end of each day, in Psalms 3&90.

These connections are a lot easier to make, and then explore the implications of in your meditations, if you start learning some of the key Latin words in the text. Indeed most translations of Psalm 3 and 90 completely lose this connection, suing words like shield or protector (which reflect the Hebrew rather than Greek-Latin tradition of the text) for 'susceptor' rather than upholder or sustainer. So if you an Oblate, or otherwise a follower of St Benedict, learning the Latin will help you understand the Rule.

(3)

Seeing the connections to the other psalms of each day/hour: St Benedict has also, in my view, built in a lot of horizontal and vertical linkages around key words, phrases and ideas into his Office - some 'memes' appear far more frequently on particular days or in particular hours than you would expect.

This reflects, in my view, the programmatic nature of St Benedict's Office, built around the seven days of creation, connected to events in Old Testament history, which in turn foreshadow events in the life of Christ. St Bede, for example, sees the division of the waters on day two of creation as connected to Noah's Ark, which in turn is connected by St Peter to baptism (1 Peter 3:20). St Benedict's Office reflects this idea with a strong concentration of images associated with baptism. We consciously or unconsciously make those links, I think, as we say the Office week after week, year after year. But again, many of those recurring words and phrases are often translated in quite different ways between psalms in English, and so the connections are often lost in translation.

(4)

Seeing the connections to Scripture: The psalms are also quoted frequently throughout Scripture, but above all in the New Testament. But the version they are quoted in is not the received Hebrew text we know today, but rather the Septuagint Greek version, reflected in the Vulgate Latin. If you want to recognise these quotes, or track them back as part of your

lectio divina, you will find it much easier if you have learnt the psalms in Latin.

(5)

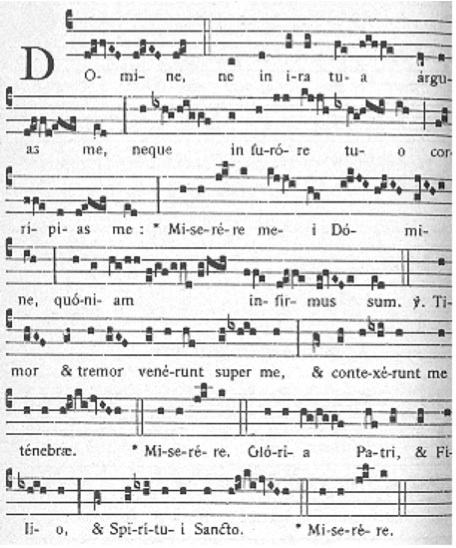

Singing the Office: Latin is also essential if you want to sing the Office using Gregorian chant, or to get the most out of others singing it, for example when you visit a traditional monastery.

Convinced?! Start slow...

If I've convinced you, there is still, of course,a practical problem (unless you have previously studied Latin and probably even then), namely the steep learning curve involved. Here are some suggestions for getting around that.

(1)

Start with a small number of psalms. Try starting with perhaps three psalms a night (the same number as the Little Office of Our Lady for example), perhaps saying the same three psalms for a couple of weeks until you know them.

(2)

Start in English then swap to Latin. If you have little or no Latin, start by saying them in English but using a very literal translation of the Vulgate, viz the Douay-Rheims so you get a general sense of what the psalms are about.

While you are doing that, start working on how to pronounce the Latin correctly. You can a pronunciation guide

here. and recordings of the psalms being read in Latin on youtube. Then switch to the Latin, working on just saying it, and preferably singing it on one note until you can say it fluently.

(3)

Pick out key words and phrases. Then gradually continue to build your understanding by working with a dictionary, picking out key words and phrases. Britt's

Dictionary of the Psalter is an extremely useful source, but if you don't have much or any Latin, working out what the root word of the Latin form is can be tricky. A great online tool that gets around this problem, as well as linking to a much more extensive dictionary, is

Perseus.

(4)

Dig further. The next stage (over time) is to read a good commentary or two on each psalm. And really this one applies no matter what language you are using!

(5)

Build up gradually. How many psalms you do using this process will depend on your starting point knowledge and how much time you can devote to learning them. If you are starting from absolutely no knowledge of Latin or the psalms, for example, you could just say the same three psalms each night for a few weeks, until you learn those, then gradually add three more perhaps from the next day of the week, until you have three of each days Matins psalms under your belt.

Then start on the next three of each days sequence, until you can say them on a four week rotation.

Then maybe try a two week rotation...

Not convinced?

Up to you of course - but either way I will start looking at the various books in the next post or two.

The choices basically fall into four categories:

- breviaries - contain all of the texts you need for the Office;

- Matins only books/resources - contain some or all of the texts you need for Matins;

- psalters - technically psalter just means a book of psalms, but it is usually used to mean the psalms interspersed with the prayers and other texts of the Office; and

- psalms translations - the book of psalms in numerical order in various translations.

Psalm translations in numerical order, whether the Vulgate or in the vernacular, can be pretty useful for the Office, for example for use on feasts when the normal daily psalms are not used. I don't plan however, on going through these, but will instead focus firstly on the various psalters that can be used to say Matins.

Further reading:

Magisterial commentary and decisions

Pope Saint John XXIII, Apostolic Constitution On the Study of Latin,

Veterum Sapientia 1962

Pope Blessed Paul VI,

Sacrificium Laudis 1966

Pope Saint John Paul II, Allocution

Libenter vos salutamus 27 November 1978

Pope Benedict XVI, Moto Proprio Establishing the Pontifical Academy for Latin, Latina Lingua 2012

Some excellent posts on reasons for using Latin

Pluscarden Benedictines

Carmelites of Michigan